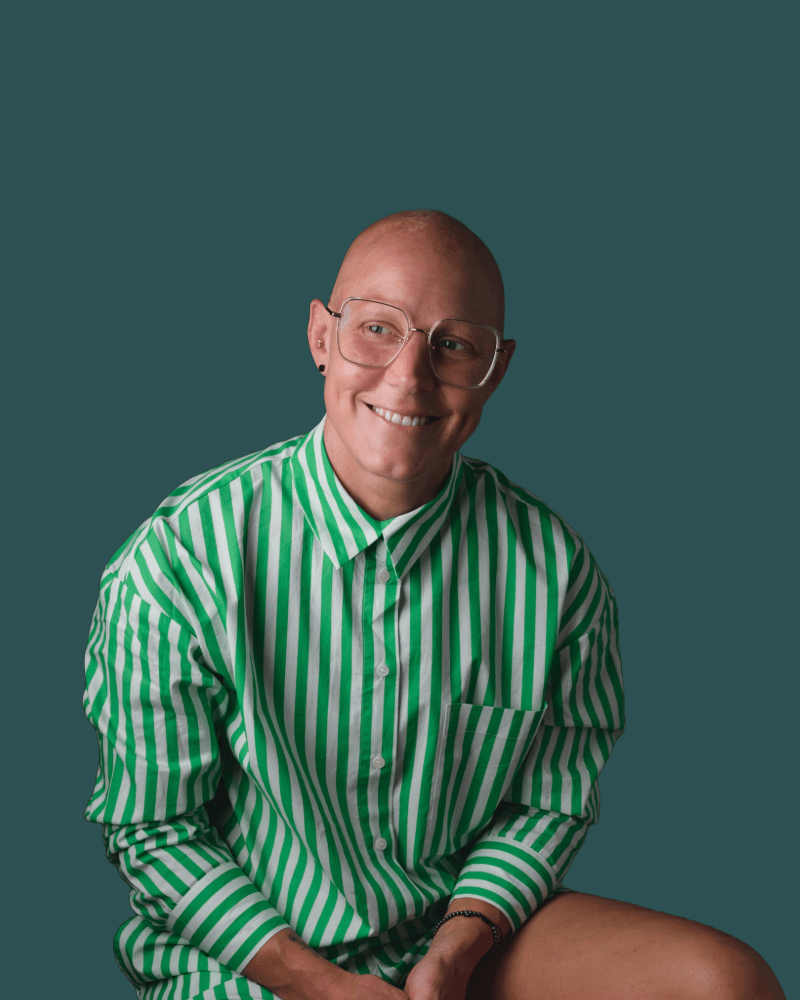

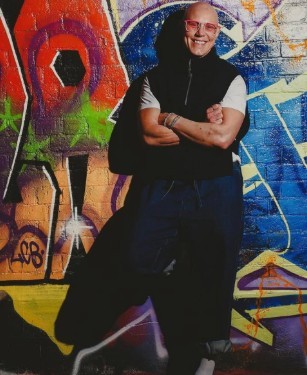

Heather Fisher: A Champion of Resilience and Authenticity

Heather Fisher, a Rugby World Cup winner, Olympian, and former GB bobsledder, has faced immense adversity to become a symbol of strength and inspiration. Overcoming teenage anorexia and a life-altering spinal injury that left her in a full-body cast for 18 months, Heather defied the odds to return to elite sports. Competing in five Rugby World Cups, winning the 2014 title, and representing Team GB at the Rio 2016 Olympics, she embodies unwavering determination and excellence.

Now retired from competition, Heather channels her passion into motivational speaking, media appearances, and advocacy. Known for her stints on Celebrity SAS Who Dares Wins and Go Hard or Go Home, she uses her platform to empower others to embrace their authentic selves. As an LGBT advocate and charity fundraiser, Heather inspires by sharing her journey of resilience and by fostering change for those facing challenges, including alopecia and autism.

What first sparked your passion for sports, and how did rugby become your focus?

Rugby became my focus because it was my escape from my home life. It was my way of distracting myself from the turbulent shambles of childhood. I just felt free when I played sports. It was difficult when I first set out because I had anorexia as a young girl, and my first ever sport was rowing which was very much about how women looked and were perceived. Strong women weren’t a thing back then, so I didn’t fit in. But sport gave me so much direction. If I’m honest, rugby was just the sport, but I did a lot of martial arts, cycling, and running, I did a lot of sports but ended up in rugby. My step-father, Mike Lord, played for England Schoolboys back in the day. I came back from school and asked him to teach me how to pass and how to tackle. I was so bad at tackling! I had no confidence and off the back of anorexia it was tough confidence-wise, I found it hard as a young girl, especially in a male-dominated sport where there wasn’t the setup. I had to go all the way to Oxford to find my first-ever club, so it was challenging. Once I was on the pathway, I found it supportive, and I suppose I found a place where I fit in with other like-minded people. I had so much pain and emotion from my childhood and my parent’s divorce, which led me through my career and I just channelled it. When I ran out of emotion was when I decided to step back from sport, because I didn’t have the same drive. I played sports to be someone, to challenge myself and to be the very best that I could be. I remember having that mindset from 12/13 years old. My dream was always to be an Olympic athlete. I used to see Denise Lewis on TV, and watch the Olympics and think “Wow”! How do I be there? I started my mission but then fell into the trap of anorexia along the way and got quite ill, my parents divorced and I got a bit lost. But sport gave me something to aim for, and gave me direction and focus which is what I needed as a young girl.

How did your experience with anorexia as a teenager shape your journey into competitive sports?

Anorexia did shape my career. I don’t think any disorder ever leaves you. It’s so challenging, and the most stubborn, strong characters struggle with their eating. I think you have to be that because you are denying what your body needs. I wanted food but I was just so stubborn. It started without me knowing, and before I knew it I was in this trap of anorexia. I was just skin and bone. You didn’t see strong women so I didn’t feel like I wanted to be muscular, but I ended up being muscular because of my sport. But I felt like I had to look a certain way as a woman. Throughout my whole school life, I was stopped from doing Physical Education, stopped from walking to school, I had to see psychologists doctors, and nutritionists. I had to get weighed every night from Monday to Thursday after school. They threatened to put me into a psychiatric ward, where I would get fed on a drip. The turning point for me was when I went to see a nutritionist. It only takes one voice to change your life. I remember walking into his office and he said ‘Heather, what do you want to be when you’re older?’ and I said ‘An athlete’. I didn’t admit it to anybody because my childhood was so turbulent and I was unsettled. He said to me ‘You won’t be an athlete unless you eat’. It was as simple as that. I went home and started eating, and before I knew it I was on the pathway. The truth is, though, it’s never really left me. Losing my hair as well was difficult because I didn’t like what I was seeing back in the mirror. I never really fitted in and even as a rugby player I was more of an athlete than a rugby player. I didn’t have a drinking mentality and I had always been very strong so perceived very differently.

People want athletes to look a certain way, and when you wear a skin-tight England shirt if you’re bloated you can still look big even if you are in good shape. As an athlete, you never want to feel that. I’ve been through times where we were selected just for our six-packs and what we looked like, and that’s mad. At the Olympic Games I hardly ever ate because I didn’t want to look a certain way, and that’s crazy when it’s the business end of the competition and you want to win a medal. The truth is, anorexia never really leaves you. It shaped my whole journey. England never knew that I had an eating disorder, and we were getting “fat tested” every month, it makes it difficult. There was a time in my career when I was 32, and I was speaking to a nutritionist. My fat percentage was low anyway, but I said to him ‘I think it’s too low and I want to bring it up a little bit because I don’t think I can perform with this little fat on me, I feel like I need more’. So there are conversations like that behind the scenes that when you’re sensitive towards an eating disorder it can be tough. And when you’ve got no hair and you can’t change how you physically look, then you feel the need to look the part elsewhere. So I made adjustments to my diet and my lifestyle because of that. That wasn’t easy.

What inner strength helped you rebuild after breaking your back and coping with alopecia?

As an athlete, I thought I was invincible. But breaking my back was the first time in my career that I realised I wasn’t. I don’t break, and I’ve just broken. After a year and a half in plaster and being told I wouldn’t play again. They said if you play again you could be paralysed, but I took that risk. I would rather know what I could have been, rather than always wondering what I could have been. So I took that gamble. I remember saying to my parents ‘This is what I’ve been told, I’m going to play’. It was really important that I could prove to myself that I wasn’t broken, and an injury wasn’t going to stop me. But I also realise there are players out there who have broken their back and not come back. I had to learn to crawl, then stand, then walk, to even get close to returning to rugby. Sport is brutal, and at the end of the day, you’re just a human body. I broke it in 4 places; it was 18 months in plaster then another year of rehabilitation. I lost my hair, my nickname was ‘Jelly Belly’ because I’d put so much weight on and I was bald so I looked like a boiled egg. I joke about it, but the truth is, I didn’t identify with who I was, and there was no time to identify with who I was because I had just broken my back and I had to get back to playing for England. There was no time to think about my hair loss. But in 2016 before the Olympics that was when I realised that I didn’t know who I was. I was up against a coach who didn’t like me who challenged me over everything, who told me to fit in with everyone else. I don’t know how to fit in. I was just being myself and if that’s not enough then I don’t know how else to be. When that’s your leadership, you question who you are. And under pressure, you have to know who you are. The more you know who you are, the better you’re able to perform under pressure, and I believe that in every walk of life. I saw a mindset coach and he helped to identify who I was from the inside out. Hair or no hair would not define me, but at the same time, it’s defined my whole life. I didn’t go out for five years. I wouldn’t be seen, I wouldn’t do any interviews I felt ashamed and disgusting. People are so quick to judge. When people looked at me they wouldn’t see a human being, they’d look at me like ‘What’s that?’. People question my gender. I get it all the time. The inner strength came from nothing that was going to break me. I was going to define my journey. I was always set on that from when I was a young girl. I think what’s difficult is that in sports we control freaks and we control our performance. But we are in the most chaotic, unpredictable environment and anything can happen, so you’re out of control. You have to be able to adapt so quickly. My inner strength has always come from wanting to be better. I didn’t give myself a choice.

What did winning the 2014 Rugby World Cup mean to you on a personal level?

I was a dual athlete. So I played rugby 7s and 15s, so I would play in a 7s World Cup, then a 15s World Cup, then a 7s World Cup etc. That came with its challenges because now they are separate but back then you had to go from being a back row player weighing 75-80kg to a 7s player who is sprinting around the pitch at 70kg, it just doesn’t work. So after quite a big knee injury, I was thrown back into training and the World Cup squad. I hadn’t played in the Six Nations because England had taken me to play in 7s, so I wasn’t match-fit for 15s. The coach changed and we turned into playing by numbers, and I wasn’t a system player I played with my instincts, and played what I felt. I didn’t play by standing somewhere because someone had told me to stand somewhere. Everything had to happen in a completely linear way, which did not work for me. In the 2014 World Cup, it became about a system and this is how we are going to play. I struggled to fit into that game plan and I wasn’t selected for the final. It was hard because I knew that I was good enough, but I also knew that I wasn’t good enough for the system as a team. So yes, it was great to play in a World Cup, it was great to play with that team, but the truth is a medal doesn’t define you. It didn’t change my life; it didn’t fulfil my dream, because my passion as a young girl was to be an Olympian, but it was never to win a World Cup. The medals are irrelevant, because if I wasn’t at my best then the rest was irrelevant. The best medals I won were when I was at my absolute best, or we as a team were at our best. Sometimes we would lose a semi-final or a final, and actually, I knew I had played my absolute best, and they’re the moments that I’m proud of myself. But it was amazing to play with all those players, I’ve been to five World Cups and to win one was amazing. But we won the World Cup and then it was on to the next thing. That’s the thing in sport, you’re always looking ahead to the next match or the next competition, there’s always someone coming to try and get your shirt. There’s always someone chasing, and there’s always something to chase.

What drives you to take on intense challenges like Celebrity SAS Who Dares Wins and Go Hard or Go Home?

SAS was tough! I left rugby because I was mentally broken. I had a mental breakdown aged 34 and suddenly turned up to pre-season training and I wasn’t ready. I thought ‘How am I 34, with no money, no car, no mortgage, and nothing to my name’. I have a great reputation and get to travel the world playing for England, but I have no family, and I’ve not settled with a partner, what the hell? A lot of it comes down to money, because money provides you with opportunity, and opportunity allows you to go on holiday, relax when you need to recover, and allows you to start a family. I didn’t have that because we weren’t paid the same as guys so it was always a sacrifice. So at age 34, I turned up to pre-season and I sat down with my coach Simon Amor, who was a great guy, and said ‘I can’t be here anymore’. People didn’t like hearing it, I struggled with it myself, but I wasn’t fit for anything. I cried every day for 8 months, and it was a win if I got out of bed. I didn’t eat, my anorexia kicked back in. I had no drive, I had no passion. I was completely lost. What got me through was not being defined by a moment. I had been in sport a long time, bounced between Rugby 7s and 15s, some bobsleigh as well, and I had never stopped. I always got back on the horse and went again. There’s only so long you can keep high performance up if you haven’t got everything in place to support you. I became quite exposed in the end, I had to strip everything back and go and recover.

Celebrity SAS was the first time I smiled in months. We were on the bus going to the first camp, I turned round to Andrea McLean and I smiled, and I realised it was the first time I had smiled in months. I lost my smile, I lost my way. I love to be challenged and pushed, if not I get bored. I played for England day in and day out, but because things weren’t getting any better around us financially then that affected opportunity. I think as a senior player I was just getting a bit bored and a bit stuck. So SAS was brilliant. It pushed me mentally, and physically, and I learned that I am true to who I am, and I stay true to my values and I push myself to my limits. It confirmed that I knew who I was. I didn’t go on to win it; I went on because I wanted to make a difference. I’d never watched the programme; I didn’t know what I was getting myself into, so it was all a bit of a shock! And it gave me a new chapter. Go Hard or Go Home was another show that I loved making, I love making a difference, and it allowed me to pass on my knowledge and help other people and you can’t put a price on that.

How do you view your role as an LGBT advocate and public figure for those facing personal challenges?

I don’t view myself as an LGBT advocate; I don’t put a label on myself. I’m just ‘Fish’! I connect to people, it could be a guy it could be a girl. I currently have a partner and I’m really happy with her, and I’ve never really labelled myself as anything. I feel like people label themselves, they must be this or they must be that. People like to be labelled, and people like to label people, but the truth is when you lose your hair and you’re questioned on your identity anyway, people don’t know if you’re a guy or a girl. I’m treated differently when people think I’m a guy, and I’m treated differently when they know I’m a girl, and the truth is I’m just Fish.

What core lessons of resilience do you share from your career as an elite athlete?

The biggest one is bounceability and strength in who you are. Knowing who you are and having emotional intelligence are the most important things. People love a job, status, and a role. But having emotional intelligence and knowing yourself and how to treat people around you, you get better performance from it because people want to work with you and for you and do more. For me, that’s key. Be a nice person all the time. You’ve got to learn to bounce. There’s always going to be obstacles in your way and you’ve got to learn to bounce past them. It’s difficult. There are different types of resilience, there was the resilience I had in rugby, where I knew my pitch, and I knew where the white lines were. I knew the rules, I knew where I could break them, and I knew myself as an athlete so I knew my strengths. I think what is different now coming to the entertainment industry is that I don’t know my pitch yet. I don’t know my strengths. I know my weaknesses but I don’t know what I’m good at yet because I haven’t found it. I’m finding out what type of player I am in the entertainment industry. And that’s a different type of resilience because I just don’t know yet. There’s a lot to be said for being brave, being bold, and putting yourself out there. Stand on your own two feet and trust yourself. But trusting yourself comes from knowing yourself, and being consistently conscious about who you are and how you treat people and how you make people around you feel.

What inspired your commitment to charity work, especially for young people with autism and those with alopecia?

I wouldn’t be where I was if it wasn’t for all the doctors, physios, mentors, psychologists, mindset coaches, friends, teammates. I wouldn’t be where I was if I didn’t have amazing people working with me behind the scenes. Every time I put my England shirt on I can honestly say, I represented everyone who patched me back together. I had some big injuries, I’ve taken some gambles, I’ve switched sports, I’ve bounced around, and I was trusted to do that. That comes from amazing people being around me. So when it comes to charity work it’s no different. I’m in a position where I can give back, and if I can give back and help others feel better: that’s what it’s about! I’ve never really fitted in, and since working with Good Vibes Only Talent, and understanding myself in terms of my ADHD, and my brother has autism, and understand that I’ve never really fitted in; there should be space for everybody.

How has your drive as an athlete translated into your role as a motivational speaker and media personality?

I just want to be the best I can be. It’s all about reaching my potential. Whatever shoes I put on, I want to fill them, start to walk in them, then run in them. It’s pretty simple.

What advice would you give your younger self facing early struggles, and what message do you want to leave with young athletes today?

Trust yourself. Trust yourself that you’re strong enough to get through anything. Trust yourself that you’ll always be okay. The answer will come, or you’ll find your answer. We have so many challenges around us that we have to face, some of which we don’t even expect to come. I’m quite innocent, in that I’m just me. I say or do things and I don’t think because I’m just being my authentic self. That’s not an excuse, I’m just being honest. I believe that everyone is like that too, but then things happen, or I’m misunderstood, but taking time to understand someone is so important. Being brave is not always what I want to be, being strong is not always what I want to be, but we have to pitch in and help each other. I wish I had more people who were part of my team now. If anyone wants to be part of my team now let me know! It’s understanding who I fit in with, and who’s going to challenge me. My advice to my younger self is to trust that you will always be ok, and will always find a way to win.

APPLY TODAY

100 Top Global Women Entrepreneurs – Global Woman Magazine

Our Journey in 12 Months:

Our Journey in 12 Months – Global Woman Magazine

5 Things That Show Money is Not Evil:

5 Things to Show That Money Is Not Evil – Global Woman Magazine

Global Man Magazine Page:

Global Woman, Global Man: Socials:

Global Woman Magazine (@global_woman.magazine) • Instagram photos and videos